[This article was originally published in LinkedIn on September 26, 2016.]

□ Should we let our kids choose any college major they want? Or should we guide them towards safe, traditional majors such as engineering, business, and pre-med? □

It’s that time of the year again. And no, I am not talking about the American football season (although college football is a huge deal in the Satrio household). I am talking about the time when high school seniors across the US start filling out their college applications. My son, Austin, the youngest one in the family, is doing just that nowadays.

Among the Asian-American community where I live, parents ask each other whenever they gather. “Which universities is your son/daughter applying to?” The University of Texas at Austin, at Dallas, and Texas A&M University are usually in the list, sometimes joined by a few out-of-state and private universities. Then comes the next question, “What does he/she want to study?” Engineering and pre-med majors will get unequivocal approvals. Business and architecture are acceptable, too. Offbeat majors such as music, meteorology, or radio-TV-film, on the other hand, are often met with blank stares and a few seconds of silence. Eventually comes the follow up: “Hmm … what is he/she going to do with that?”

This discussion inevitably turns into a friendly-yet-passionate argument of “pursuing your dream” vs. “making a good living.” My long-time friend Tony – who is a strong proponent of the latter, pragmatist camp – puts the blame squarely on the high school counselors. “They tell the kids: follow your dreams, follow your dreams. Then the kids graduate with a degree in history or English, along with loads of college debt, and they find out they can’t find a decent job, let alone pay their debt.” Although I don’t agree with him, he certainly does have a point. Just in my great state of Texas, the average student loan debt of a college graduate is $22,800, and that is below the national average [1]. (A recent public radio program even featured a music graduate who has trouble earning enough money to pay off her student loan debt [2] – more on her later.) Still, my other friends from the idealist, “pursue your dream” camp would reply, “Wait a minute, Tony! What is your definition of a decent job?”

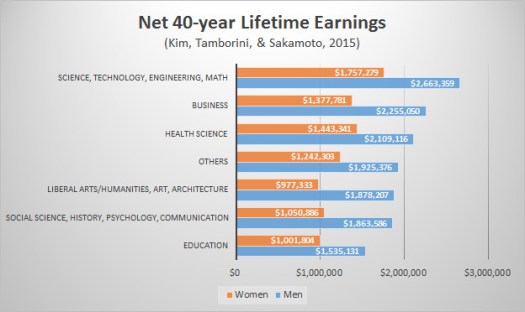

The debate of “pursuing your dream” and “making a good living” also flares up in my own family from time to time. I lean more towards the idealist camp while my wife, Lili, is the other way around. “America is a land of opportunity,” I say, “If you are really good at something, you can make a good living.” Lili is not convinced. So while she is away on a trip abroad, the rational man in me has set out to look for data to back up my point. “Does having a degree in STEM, health science, or business really translate to higher earnings compared to other degrees?” I wondered. I am especially interested to see the cumulative earnings over one’s lifetime, and not just the salary level of the first job. After all, I see a wide variation of career success among my friends with an electrical engineering degree. Luckily, three researchers just published such a study.

Dr. Kim, Dr. Tamborini, and Dr. Sakamoto examined the earnings and field of study records of 24,320 men and 25,039 women in the US from 1982 to 2008 [3]. Slightly more than half held at least a bachelor’s degree, while the rest were high school graduates (for comparison). The researcher estimated the 40-year lifetime earnings (from age 20 to 59) of people with bachelor degree in seven fields of study. The results are shown below. To my dismay, it shows that people with a bachelor degree in STEM, business, and health science majors do earn more than people with other bachelor degrees – even in this land of opportunity – which would support Lili’s argument.

Although the data did moderate my position, I am still not ready to embrace the pragmatist camp. First, 76% of college freshmen now plan to continue to the graduate school [4], and the same study from Dr. Kim et al. shows that a graduate degree in medicine and dentistry will propel one’s lifetime earnings to $5.25M, way above the other degrees. While we often assume that people who enter medical schools have pre-med or biological sciences majors, the fact is that only about half actually do [5]. The other half comes from various majors including social sciences and humanities. Ditto for the next two highest income-producing graduate degrees (business and law). Second, the one variable that determines income more than anything else is occupation. While some majors are tightly connected to one’s occupation (e.g. 82% of nursing majors work as health professionals), many don’t. Among the US history majors, 23% work in management, 16% in sales, and 9% in computer services [6] – who would have guessed?

As informative as the statistics are, they can only tell about the past and not the future. We live in a rapidly-changing world, and it is very difficult to predict what occupations will be in high-demand 20 or even 10 years from now. When I studied electrical engineering in the early 1990s, nobody told me that mobile communication would be a booming industry. I stumbled into it by serendipity. Smartphone app designer, social media director, and wind farm engineer jobs didn’t exist ten years ago [7]. As robots enter our homes and offices, robotics companies now need social scientists to give robots social skills and make them more human.

Above all, we are all given different talents and passions for a reason. The world needs philosophers and writers, naturalists and conservationists, and artists and musicians as much as it needs computer engineers, heart surgeons, and financial experts. Many of the most influential people in human history – and some of the happiest people I’ve met – have no big lifetime earnings to show for, yet the world is so much better because of them. The young music graduate, who I mentioned earlier, went back to school and got a second degree in business to earn better income. She tried her hands on a couple of office jobs but “just couldn’t leave music behind.” So she went back to music. I would venture to say that when all is said and done, she won’t regret her decision. As Oliver Wendell Holmes once said, “Alas for those that never sing, but die with all their music in them!”

In the end, I may never persuade a staunch pragmatist like Tony, but hopefully I can convince my wife. I’ll certainly try when she comes back.

Epilogue

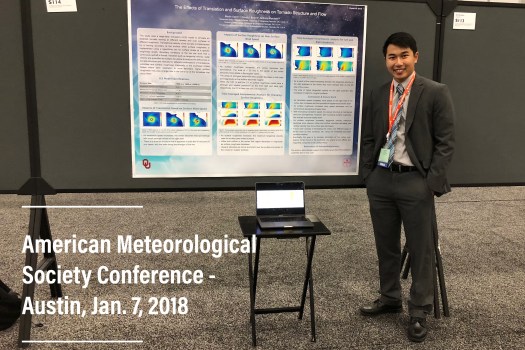

Since the article was published in 2016, my son Austin has entered the University of Oklahoma. His current major is neuroscience, but after a year of soul-searching, he is planning to switch to religious studies major next semester. His older brother Martin is a meteorologist, and his older sister Dea is an optometrist. None of them wanted to be a boring electrical engineer like their dad 🙂.

Further Readings

1. Cadik, E. (2014, December 11). Texas student loan debt is getting even worse. Burnt Orange Report.

2. Collins. C. (2016, September 20). One crisis away: Musician with two bachelor’s degrees drowns in $38k of student loan debt. KERA News.

3. Kim, C., Tamborini, C. R., & Sakamoto, A. (2015). Field of study in college and lifetime earnings in the United States. Sociology of Education, 88(4), 320-339.

4. Eagan, K., Stolzenberg, E. B., Ramirez, J. J., Aragon, M. C., Suchard, M. R., & Hurtado, S. (2014). The American freshman: National norms fall 2014. Los Angeles: Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA.

5. Ross, K. M. (2016, August 23). Infographic: 4 questions about undergraduate majors for medical school. U.S. News & World Report.

6. Carnevale, A. P., Strohl, J., & Melton, M. (2016). What’s it worth? The economic value of college majors. Center on Education and the Workforce, Georgetown University.

7. Buhl, L. (n.d.). Newest professions, growing salaries. Monster.